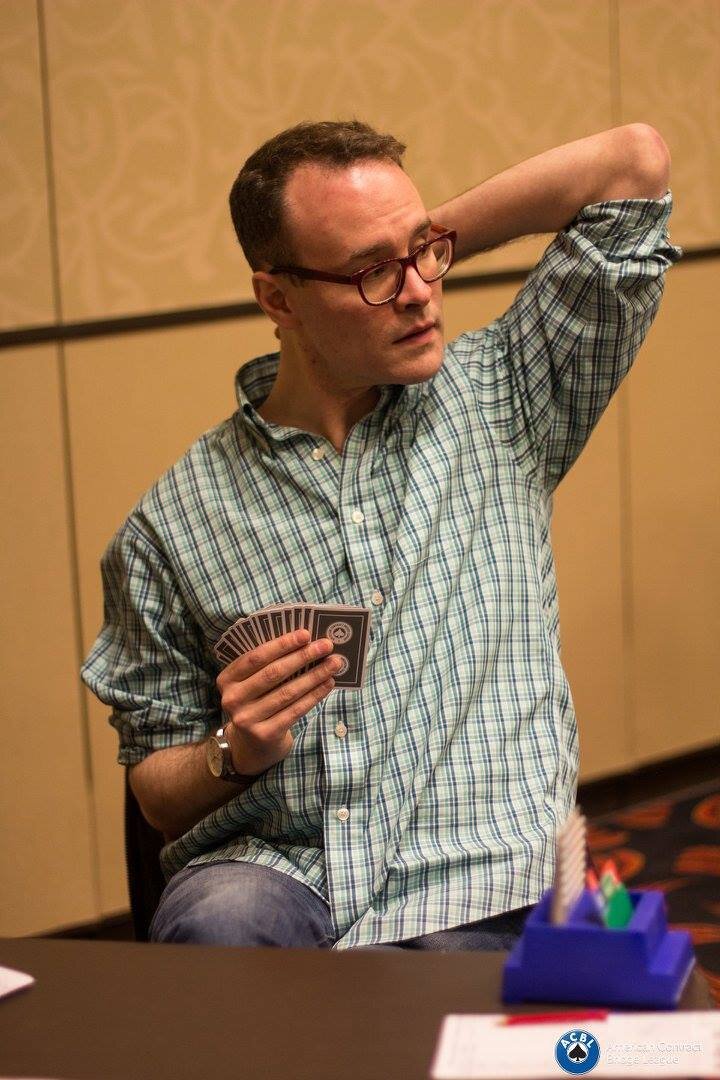

EPISODE 23: Chris Willenken

Not all professional bridge players are world class. I will comfortably posit that Chris Willenken is. Having watched a director ask Chris about a bidding problem at an NABC I've been dumbfounded about how much Chris knows with just a few words introduction. Demand for playing lessons with him has skyrocketed during COVID-19 as bridge players seek to improve their games online.

I love the role Chris' mother played in helping him find this lifelong pursuit. Find out how she and bridge communities in both the Poconos and New York City's initial nurturing helped turn Chris into a top American expert.

Episode Highlights:

2:45- How Chris started playing bridge through his mother

9:05- The Collegiate School and Manhattan Bridge Club

13:40- Chris’ relationship with one of his first partners

16:00- Chris’ quotation on Ernest Hemingway to describe how he started his bridge professional career

20:05- Chris’ heartbreaking story about losing the Blue Ribbons Pair on the last board

25:20- Chris’ story of a funny hand played with Roy Welland

30:20- Chris’ story of making it to the semifinals of the Rosenblum with Michael Rosenberg, Chris’s hall of fame bridge partner for five year

38:20- Chris’ mindset on all his incredibly close calls in winning major tournaments

41:30- Chris’ answer to when he felt he could be considered a great bridge player

47:10- Chris’ epic history with parliamentary debate at Williams College

Amanda Amert, Chris’s debate partner at Williams.

51:45- Chris’ style of bride with his current partner, Jan Jansma

57:15- How Chris views the use of deception in bridge

1:04:50- How Chris decides with his partner their bidding system

1:07:10- Chris’ family and quarantine time

1:15:50- Is Chris better than Kalita???

1:18:45- Youth Bridge Association

John McAllister: Let's start out with your mother. You told me recently during a coaching session, I take bridge instruction. I've done some, played some online with you where you're teaching me bridge. During that conversation, you said that you started playing bridge because of your mother.

Chris Willenken: That is true. My mom is of a generation where in college, almost everybody knew a little bit of bridge, it seems. To hear her tell it, you'd walk into the student center and there would be multiple games of bridge going on at any given time. She had played a little bit at that point, probably didn't learn in a disciplined way, like we all did, and probably didn't always learn the right way to play bridge because she was getting taught by her friends who probably just got taught by some other students, but they were just having fun with the game. It was part of the culture, it seems. Everybody just felt like it was a normal thing to be doing in their spare time. She had played and enjoyed it in college, and then had a kitchen table game when I was a small child.

At some point when I was a bored teenager over a summer, she said, "Hey, you know, you like all these other games, you really should check out this bridge game." Why don't you go get a book out of the library?" I went to the library, and at this point, we were in the Poconos. I went to the local library, which did have a bridge book. It was Charles Goren's big book of bridge, the 1953 edition. That's how I learned to play bridge four card majors. I learned some new-fangled, 1953 conventions, like negative doubles, and I was off to the races.

John: It impresses me that you remember specifically that it was the 1953 edition. Chris: Well, I think of that fact, it was not lost on me at the time that that was

strange. That's why it stuck with me.

[laughs]

John: You were 13, and this was the summer before eighth grade, or?

Chris: I was 15, I believe. Although interestingly, I have less of a coherent grasp on the year it actually was than the the year of publication of the book, I think it was the summer of 1991, but I wouldn't swear to that.

John: There's some things to elaborate on that. This is in the Poconos, and you said that soon after getting the book, you went to the local bridge club and played, and then the next time you went to the local bridge club and played, the club had one life master and they arranged for that life master to play with you.

Chris: Yes. Having a young player at that time in that game was so novel that everybody just really enjoyed having me around, which I know has not been the universal reception for young players in this game, I think it varies so much based on the bridge community one encounters, whether they're extra welcoming or maybe resenting an outsider, perhaps a brash outsider in my case, particularly, and that can really shape a whole life of bridge, because I'm sure that if I had gotten a cold shoulder or even worse, nasty greeting, that just would have been the end of it. I was just a shy teenager. That probably would have finished me off, but the converse happened. I was treated so warmly that I really fell in love with the game and pursued it.

John: How long into this Goren book did you end up going to the bridge club, and what was that process like?

Chris: That, I have to say, I'm pretty sure I got all the way through it before I went to the club, and I was a very, very shy teenager, painfully shy, which might surprise those who know me now, or maybe not, I still have some introverted tendencies. It was my mother who actually arranged the game for me. She called and said, "Hey, I've got this son who's kind of interested. Can you find them a partner?" She drove me there because I did not know how to drive. Really, all the credit for--

John: When you say you didn't know how to drive, were you old enough to have a driver's license?

Chris: I was 15. I might, in theory, have been old enough to have a learner's permit in New York. I don't know what the rules were in Pennsylvania, but I've always been scared of driving. I actually got my driver's license in 2001. I was 26. I was-- [silence]

John: It sounds like a classic New York City kid to be. When I was 15 years old, granted, I lived on a farm in Virginia, but I was chomping at the bit to get behind the wheel. [chuckles]

Chris: My peripheral vision has never been that great. The rear view mirror was always optional for me. It's probably a little better that I'm retired.

John: At this time, you were going to the oldest school in the United States, Collegiate school. Were you a survivor, as they call them?

Chris: Oh, wow. You really have done your research. I was not a survivor, which are those who spent their entire pre-college years at Collegiate. I transferred there in the third grade, and then through my senior year of high school.

John: When you came back to school, was there any bridge activity at Collegiate, or did you end up going to honors or something like that? What was the next step?

Chris: I actually did rustle up a kitchen table game, if you will, at Collegiate. We didn't really know what we were doing. The idea of bidding for more than nine tricks on any hand was just completely incomprehensible to have the idea that somebody could take more than nine tricks and a hand was pretty much a stretch. I did have that as part of my early experience.

Fairly quickly, and again, with my mother's prodding, and phoning ahead and all that, I ended up at the Manhattan bridge club, which was, at the time, in a basement on West 73rd Street, I believe. We shared the space with some Hungarian gamblers. I'm not still sure to this day exactly what card game they were playing. I got very lucky there, because at the time, there was a really vibrant junior bridge community in New York City, and it was centered at the Manhattan bridge club.

At that time, there were players like Blair Seidler, Lapt Chan, who was not quite a junior but was also one of the young, hot shots. Randy Lazarus and some others. You might know some of those names, John, who were really hotshot young players and were hanging around just playing a lot of bridge. I'm not totally sure if anyone had jobs during those days. All those folks ended up eventually being respectable people with "real jobs", but they were certainly playing a lot of bridge in those days. They were really generous with their time and their advice. They'd go over hands with me, they'd play with me sometimes. That was, again, really important. I had a group of folks that I could relate to. I was 16 probably at this point, but still, even though these guys were 5, 10 years older, still that's very different for a 16-year-old than interacting with a senior citizen. It was accessible for me and really, really educational.

John: Going back to this first game in the Poconos, did you already-- you described yourself as being a little, I don't know if obnoxious is the word you use, but that you were sure of yourself at bridge. Do you remember that being the case in that first--

Chris: Well, most teenage kids, certainly boys posture a lot. I don't recall. Actually, one strength that I have in bridge is my ability to not just have an opinion, but also to handicap for my certainty about that opinion. Some stuff, I'm pretty confident I know, and so I don't revisit it too often, but then there are other things I'm less sure of and I spend my time and energy re-examining those. I don't feel like at bridge in general. I'm overconfident. I'm certainly confident, probably somewhat realistic, and I think at that time it was probably the same, but of course, 16-year-old kid, you're not going to show any weakness to the outside world. That was never really an issue in the Poconos game because there were no alphas there, everybody was just really nice and really laid back, and that was actually a really nurturing environment, there was no need to assert myself as an individual, as teenagers might often have to do.

John: Has the guy from the Poconos, the life master you play with, is he abreast of your bridge career to this day?

Chris: Yes, that's actually sort of a sad thing, which is I've just completely lost track of him over the years, and I've tried to find him on the internet. I put quite a lot of time into that with no success.

John: Wow.

Chris: That is a little sad. I would have liked to hunt him down and go over some

hands like in the old days.

John: [laughs] Well, maybe somebody from this podcast will be able to help you in that regard.

Chris: That's a good point. His name was Steven J. Danko, and he lived in Hemlock Farms, Pennsylvania, and this would have been in the early '90s.

John: Did you play with Steven more than once?

Chris: Yes, he actually started running his own game in a nearby town, and he would drive me to that game. This is some later summers, I don't remember exactly the timeline. He would drive me to the game. Sometimes I would play there with him, sometimes with a customer who he just needed a partner for, so I was just the utility guy. It was great because it was about a half an hour trip back to my place, and he would drive me back and we would talk about the hands.

[laughter]

I can't tell you how many times we would drive half an hour and then sit another half an hour in the driveway still talking about the hands.

[laughter]

Those were good times.

John: Do you think at that time, reminiscing about going over the hands, do you think you were already better than him?

Chris: No, definitely not. He was a reasonable player. It's hard for me, looking back, to know exactly how reasonable, but I was still starting out and he could run squeezes and end plays and things like that. He wasn't too sophisticated in the bidding, because he just wasn't part of the modern tournament scene, and of course, bidding itself was much less sophisticated everywhere in the early '90s.

John: Wow, man, that's great [laughs]. When you said customer, I thought maybe you were playing Pro, but I quickly realized that that wasn't the case. When did becoming a professional bridge player, when did that become an option, and how did that happen?

Chris: There's a Hemingway quote from The Sun Also Rises, I think, where one of the characters is asked, "How did you go bankrupt?" The answer was gradually at first, then suddenly. [laughs] I think I would give you the same answer.

[laughter]

The gradual part is that in some of the college summers, when I was already at that point, a pretty reasonable player, I would fill in in a rubber bridge club. I was a house player, so basically, if there were three people who needed a fourth for a game, I would just jump in and play for my own account, and I would also occasionally be called on to sort of help with instruction as an assistant in some of the lessons that they used to give at that club. That was my first foray into collecting money around the game of bridge, but obviously wasn't a traditional sort of playing professional relationship.

That happened to me in 2001. I had just done a three-year stint on the floor of the American Stock Exchange trading stock options. Things were not good for me in the .com bust era, so I left the floor and really didn't have any plan for what the next step was going to be. Right around that time, completely serendipitously, I think, I was contacted by a player who actually wanted help winning some of the local regional events that New York had at that time. New York used to run these reasonably prestigious multi-day knockout and pair games back in the '90s. Folks like Paul Soloway and Grant Baze would fly in with their sponsors to play in these events, and they were just large events with very strong fields. I was hired to help this player win the Goldman Pairs, which is the two-day pair game, which he had never won, and that ended up blossoming into a reasonably long term professional situation for me.

John: You did actually win the Goldman Pairs with him?

Chris: Did we win the Goldman? I don't actually think we did, but we decided to play the 2002, I think, Cavendish Pairs, and I think we were leading after three sessions of that. My partner's name, Glenn Milgrim. He's actually a really excellent player in his own right, and hopefully I had some contribution to that, but he's also extremely knowledgeable and talented player, very tough opponent. We ended up not really worrying about the Goldmans and trying to win national events instead. We came seventh in that Cavendish Pairs, and we had a number of top 10s together in national pair games, including two seconds, and a heartbreaking loss of the Blue Ribbon Pairs on literally the last hand of the event, but they were good times with a lot of good bridge. Glenn is just a fantastic human being in addition to being an excellent bridge player, so those times were really great for me. It was a great introduction to professional bridge.

John: Tell me about losing the Blue Ribbons on the last spot.

Chris: Yes, this was a fairly brutal roller coaster of an event. On day one, I had food poisoning and was not playing particularly well, and we ended up in a tie break for the last qualifying spot. We had exactly the same number of match points as someone else, and the tie had to get broken by board match, which the computers couldn't do it that time, so the directors had to break out the scores by hand and board matches against one another, however it was. We got in as the last qualifier on the first day. We had two consecutive 65% games the second day to be in third place going into the finals. We had a third 65% game in the first final session. We were now ahead of second place by two full boards and three full boards plus ahead of everyone else.

The second-place pair was Bramley and Lazard, who, as the movement fate would have it, we were fated to play in the last round. We're playing along in the evening, and I think we're doing pretty well. I feel like when we sit down at that table, we're well over 60% with that lead, and I'm feeling pretty good about it, but then Bramley asks me, "How are you doing?"

[laughter]

Just like that, and I said, "Oh, oh, that's somebody who thinks they have a chance from two boards behind." It was a two board round, and we had two bad results. The first result, Bramley and Lazard opened Flannery with an unsound hand just looking for the swing, they explained afterwards, and reached four hearts from the concealed side of the table, and basically we had to make a almost impossible defense where at trick to, with dummy having-- they reached four spades, I guess it went two diamonds past four spades. Glenn had to let his ace-king and then seeing the dummy after the opening lead, he had to switch to jack double 10 of hearts with ace 10 nine fifth in the dummy just to get a trick for my king, whereas he knew nothing about [unintelligible 00:20:05] hearts and it could be blowing up a trick. It was just an impossible play, I thought. We got a stone zero because it was not normal for them to be in-game and certainly anybody else who is in-game from the other side of

the table, which I think was more normal. It was going to start, one heart, two clubs, two spades, something like that. Anybody who was playing from the other side of the table would have been defeated easily because the switch was much more obvious seeing the dummy at the other table.

We took a stone zero on the first hand, and then on the second hand, we had an opportunity. We were now actually behind and with an opportunity to win on the last hand, by bidding a really thin slam, which I think if we had been on the same wavelength about our auction, we might have steamed into and we would have made it, but an obscure auction for our system came up and we hadn't discussed all of the inferences, and so we had a slight disagreement about whether four of our minor was forcing, and so we played four clubs instead of five clubs, which would have made us second, or six clubs which would have made us first, and so we finished fourth.

That's my hard luck, blue-ribbon pair story, but look, the opponents came back and had 66% or something like that. I think we ended up with about 54 or something like that after those two horrible scores. Then's the breaks. Normally, I would have thought being in third place, going into the final day and averaging 60% would have been enough to win, but this was just not one of those days. The hands were exciting. There were a lot of big games.

John: Wow.

Chris: That was exciting, and we did have some other-- Poor Glenn. He's still never won a national. We had another second place where we were announced as the winners by under one match point, and then there were some appeal that didn't involve either us or the second-place pair, but it changed a match point between the two pairs. We lost by 0.03 or something like that the next day. That was, I'm sure, very sad for him to leave the playing area thinking you've won and then find out the next day that there's been some minor ruling.

John: I was emailing with another-- he might have been your next professional partner, I'm not sure, but I was emailing with Roy Welland recently to ask him about, I saw that he and Sabina play optional exclusion, and I thought that sounded a really good treatment. I asked him about what they play, and he emailed me back. One of the things he said was that in a relay auction, with the help of the opponents, that he asked you for key cards, to answer optional exclusion three times before letting you play in three spades making 140. [chuckles]

Chris: Yes, that was a really incredible. That wasn't an exclusion. Roy was the first serious national sponsor to put me on his team. That was in 2007. Our first tournament was the Nashville summer nationals in 2007, the beginning of that cycle, where we were second in the Grand National teams and got to the semi-finals of the Spingold. Good debut tournament there. Roy is an amazing player. Really, really talented, and he has a lot of very interesting ideas about bidding, and these optional asks come from his system. Roy's general idea about slam bidding is that if we can find out the shape of one of the hands, and then just each hand says how good it is in context, cue bids are not that important. It doesn't matter the exact control. Sometimes it'll be a hand like that where you need the ace of a certain suit because you need to win the A's on the opening lead and then pitch all your losers. Those two hands do come up, but they're pretty rare.

Roy believes or at least believed when we were playing that it was a mistake to worry about those hands. The system was designed with a lot of bids that said, "Okay, I've heard your shape, here's what's trumps. Tell me how much you like your hand, and if you like it, also tell me your key cards along the way." These methods only came up in nominally game-forcing auctions, notionally game forcing, but the hand in question, Roy had asked the opponents had doubled. I had shown a minimum, then I believe because the auction was so low, he was able to re-ask again.

I don't remember the details of it, but he had-- the gist of it was that he had a devalued holding based on the double. He had something, king third and the suit that had been doubled, and maybe I had even shown singleton there, I don't remember, but it was some situation where he was pretty sure that his hand was no longer really a game force based on the combination of me showing my shape and the double. When I had shown a minimum minimum, it just happened that that step that I showed second minimum with was our trump suit. He was able to pass.

Some players care only about results, and Roy is super competitive, but he also loves beautiful things about the game. I think that's one of the reasons the deal excited him so much. It's just something where you launch into this game forcing relay, you're thinking maybe there's going to be a slam and then things come up just so, and you end up playing in three spades. That is actually an incredible thing about bridge, is you never know where any hand is going to take you.

John: What was the event? [unintelligible 00:26:30], match points, what?

Chris: It was [unintelligible 00:26:33]. Roy and I almost never played match points, and when we did, we did horribly because our style was ultra-aggressive, ultra, ultra aggressive. That's quite a reasonable style, but not good match points. Match points is much more of a conservative game, at least strong match points. This must have been [unintelligible 00:26:54]. I don't particularly think it was one of the really major events. I think it's such a remarkable occurrence that that could ever happen in bridge, and that's why it stuck in both of our minds. I was pretty sure what hand you were going to talk about just when you started to mention Roy and him recounting a hand to you.

John: By the way, David Laurie is the new headmaster at Collegiate. I think he's coming in this year. Previously he was the headmaster of my elementary school, alma mater, St. Anne's Belfield.

Chris: The private school world is a small world. It's not surprising in retrospect.

John: In some of the research that Michael did, back in 2012, you said your best result was getting to the semi-finals of the Rosenblum with Michael Rosenberg.

Chris: Yes, I was very proud of that result. Michael, in my second tournament together. There's some theme here, which is maybe all my partnerships, we start out with our best results. That's probably not so good. Not so good a theme. Maybe some reason for that is that when you're starting out, everyone tries to build a fence around partner. You both know that you're not on firm ground, and you make allowances, and then maybe later, it's easy to not accident proof everything so much. Maybe it's easier to start having some more silly results. That was a great tournament because Jeff Wolfson then had decided pretty much at the last minute to return to competitive bridge for this world championship.

Now, everybody, I'm sure who's listening knows Jeff as a fixture in the high-level events. He had also been a fixture in the mid-90s to the early aughts but taken quite a number of years off of serious bridge, I would say. He had a first time partnership for that event with Larry Cohen. He asked Michael and I to play, and we were joined by Ron Pachtman and [unintelligible 00:29:07] who were at that time a hotshot young pair who had relatively recently won the European open teams, and we started out pretty rocky after two days of the three day round robin. We were fairly long shot to qualify.

I think out of the 75 victory points that were available, we needed about 60 of them, give or take, looked like going into the final day. We ended up getting 72 of them and qualifying easily, and we had a rather difficult run, I would say. We had an early knockout match against Michael Kamil, I believe. Maybe not Michael Kamil on that team. Maybe Marty Fleischer and Debbie Rosenberg and some folks like that. No, I'm mixing this up. Well, I'm mixing up two events. I think we played against Mike Moss. We played a relatively tough team, maybe Debbie Rosenberg and Mike Moss and some other folks in the round of 64, not an easy draw. In the round of 32, we played the South African team that had been the finals of the most recent Olympiad. We won that match. In the round of 16, we played Cayne, which was Cayne and Michael Seamon, Balicki and Żmudziński and Lauria and Versace. We thought, at the time, it was a hard team. Now, I realized not only was it a hard team, but we were probably being cheated as well, but we did manage to ride a huge third quarter to victory in that match.

In the quarterfinals, we played Fleisher, which was Fleisher and Kamil, Martel and Stansby, Levin and Weinstein. We beat them in a match that was close the whole way. I still do remember fun hands from that one. We played Nickell in the semi- finals, where we had a very wild set of boards in the fourth quarter. Unfortunately, we lost by four. We just needed the clock to expire a little earlier or a little later maybe since that quarter will lead ping-ponged around quite a bit.

I'm very proud of that result because we really beat a lot of truly excellent teams, and gave Nickell, which is obviously the best team of the modern era, a good run for its money. I just think even most teams that win a big knockout probably don't have that many big victories on average. Usually, if you're going to get deep into one of these events, the secret to it is having somebody good lose before they get to you, just otherwise the statistics catch up with you. How many tough matches in a row, and you're ready to win, not going to be too many. I certainly was and still am extremely proud of that result. We lost the bronze medal playoff against Fantoni and Nunes. Again, this tournament definitely has a tarnish over in this way in my mind, but that doesn't really take anything away from all of the good tough matches that we played against honest teams.

John: Michael Rosenberg, he's in the pantheon. How did the two of you come to play?

Chris: Michael and I go way back. We were friends on the floor of the American Stock Exchange, when we both traded stock options there in the late '90s. We used to spend a lot of time talking about bridge, because I think one thing that anybody who knows both of us know is that we can talk until everyone else is bored, and we'll just keep going together. We knew a lot about how the other person thought about bridge. I certainly respected Michael's game.

Certainly at that time, he was established and I was not, but I guess he had come to respect my game. Andrew had Michael on his team and needed a partner for him. I've been friendly with Andrew since the mid '90s. He's also a Collegiate man. We always had a really nice relationship. He's just a great guy. That's what he thought made sense for the team. Michael agreed to try it out. We had a Spingold, and then we had that Rosenblum, and we were doing well. We stuck with it for five years.

John: Who was a better trader, you or Michael?

Chris: [laughs] It's very hard to know. He wasn't trading the same products that I

was trading, but I suspect he was probably the better trader, if I had to guess.

John: Would you say still to this day, is that rank up there as your best result, or would it be the Spingold, losing the finals of the Spingold in 2018?

Chris: It's tough to say. I think that if you measure bridge accomplishments by who you beat, that Rosenblum is still the most good teams I've beaten in one place that run to the finals. Spingold was great, but we did have the traditional luck that one has when one does get to the final, which is a lot of the seeded teams lost before we had to play them. Obviously, we beat who was in front of us. That was good, but it's all you can do really, it would be hard to say.

I think I might put finishing fourth in the world pairs with David Berkowitz in 2016. John: '14.

Chris: 2014, that's right, when we filled out a card for half an hour over dinner and just played. Basically, we had the front of the convention card filled out, and that's all we do. We just took a lot of tricks. That's a tournament where I would have liked to medal. I have concerns, to put it mildly, about one of the pairs that finished ahead of us who shall remain nameless, but there are widely suspected, I would say. In my mind, I feel like we had a bronze medal there.

John: What would it have meant if you won the Spingold in 2018?

Chris: It's a big knock on my bridge career. I've never won a so-called major Bermuda Bowl, World Championship, major team World Championships, Spingold, Vanderbilt, Reisinger. I've had a lot of close calls. I probably have the most close calls. I get dubious record of anybody who's not won. It would have been nice to get that monkey off my back. Not to be, "Oh, that guy is one of the best players who's never won." I don't like the qualifier.

I suppose in that sense, it would have been important, and of course, winning a Spingold is pretty much as good as it gets. It's probably harder than winning a Bermuda Bowl. You can't always control the outcome yourself. There's opponents and teammates and luck. I've tried as best I can to derive my satisfaction from my own play and the play of my partnership, and to have that be as independent of the result as I can without losing a competitive edge. I think I've done an okay job of that balance.

That was a disappointing loss. We were very close going into the fourth quarter. It was definitely an easily winnable match, had our team play well, but life goes on. My life is excellent. I have a great wife and just a great group of friends. Most of them come from bridge. It's an amazing community. I just try to be very positive about all the ways that I'm lucky, and then it's easy to forget a bad bridge result. It's really a small thing in the scheme of things.

John: Would winning the Blue Ribbons have qualified for a major in your mind?

Chris: Winning Blue Ribbons is nice, but it's not a major. Winning a three-day pair game requires beating up on weaker players than you. Whereas, winning a major knockout, or winning the Reisinger, requires beating up on players that are roughly equal to you. It's a different type of skill, and it's a skill that fewer people have. There are lots of folks where if their hands come up that way, they can win a three-day pair game. I think if you look at the results of three-day pair games throughout their history, you'll see a bunch of winners that are very famous, and a bunch of winners who have never come anywhere close again. Whereas, if you look at Spingold winners, it's a pretty select club. It tends to be the same small groups of folks over and over again. There are some exceptions, but many fewer.

John: I appreciate your honesty and your candor in answering those questions. Was there a point in your bridge playing career when you were like, "I can be one of the best in the world at this." What was the point when you decided that, "Man, I'm exceptionally good at bridge."? Those are my words. They might not be yours, but those are my words, for sure.

Chris: Here's how I would phrase it. At some point, a player can have a realization that they can compete against the best. It's hard to know what is a great player, but any player that can compete against the best and really give them a run for their money. That's a strong player, and my first realization of that came in 1997 in the Spingold. As I just graduated school, in May or June, whenever it was. After the summer nationals, very exciting. I had a Spingold team, which was good, solid regional experts from New York and New England. We reached the quarter finals, having upset some pretty good teams and we played Nickell there. After three quarters of the Nickell match, we were down either two or three [unintelligible 00:40:45], I don't remember what it was. Very, very exciting situation. Obviously, I remember being really nervous and our team actually played okay in the fourth quarter, but got outplayed and out-lucked. We ended up losing by something in the 30-range I think.

If you can get down to one quarter of [unintelligible 00:41:08] 16 boards against a team that's won the previous three spin goals. No question, and this is the best team in the world. You say, "Well, those 16 boards could have gone the other way." If we can beat this team on the right day, then anything is possible.

John McAllister: Were you four-handed, five-handed, six-handed.

Chris: Six-handed. I was actually playing for the US juniors at the time. While I was playing in the Spingold, I was also playing with my junior team in the morning knockouts. I would wake up at 8:00 AM or whatever it was, to play, the morning knockouts. I had the first quarter sit out every day, so I could finish the morning knockouts up at 11:30 and then eat lunch and take a nap, so I could be ready to play in the Spingold and then not fall asleep at the table. I remember that pretty well. That's the kind of thing you can easily do when you're 21 years old.

John: Who was your junior partner?

Chris: I played with Eric Greco a couple of years in the juniors. I have never entered a junior trials because those days the ACBL used to run the junior trials opposite major events. In fact, I think that the trials for that particular junior team had been run opposite the 1996 Spingold if I'm not mistaken. Eric and I had not played in the trials, but we were added to that team. That was a real pleasure for me because he was certainly one of the strongest players that I had ever played with in those days and still but certainly at that time it was-- I have played with quite a few hall of famers in the meantime, but it was really, an exceptional experience to play with them then.

John: Yes. Geoff Hampson said when I interviewed him that he's not even sure he's the best player in his partnership.

Chris: [laughs] Of course, I'm sure he and I both know a little bit more about the game today than we did, 20 plus years ago. We're probably both better players than we were then, but we played pretty well in those days and what we lacked in sophistication we made up for with naked aggression, which at a junior event you can get away with. We actually played quite well. We reached the finals of the world championships one year and then lost to the Italians, and that was really fun. It never came up for me to play with Eric again, maybe someday.

John: Are any of the Italians that you lost to like, or any of them?

Chris: They weren't, none of them are what you would think of as the famous Italians. They're good local Italian players. They've won some Italian national championships and so forth, but none of the Lavazza teams or Angelini teams or anything like that. It wasn't that level. None of them quite made that cut. Actually one of them is a fairly prominent WBF director, Bernardo Biondo, so that's a name that folks who go to the European championships, the world championships will probably know. He's probably the best known person for that team.

John: I don't recognize him by name. Going back to your mother, does your mother still play bridge to this day?

Chris: The instant I really got into the bridge community, she got out. I dragged her back for a duplicate or two in the early days, but she said I made her nervous, [chuckles] which I'm sure I did. Now she says, I don't want to be like the other Willenken in the bridge world, and I can understand that. If you're a casual player, it's easy to be subject to scrutiny if you're related to a well-known player.

John: Right. Tell me about being on the debate team at Williams, the team of the year in 1997.

Chris: [laughs] Oh, God. You're digging up all the ancient history now. When I was in college, there wasn't really bridge at Williams. I played a decent bit of OK Bridge, which was the computer bridge back in those days. The only thing, but I actually chose Williams in not in substantial part because there was no bridge community. I feared failing to graduate if there was a constantly running bridge game in the student center. I needed to find some other game to play for fun and parliamentary debate was it. The way parliamentary debate works is the so-called government side or other forms of debate might call the affirmative proposes a case, and in parliamentary debate, it can be essentially case.

The only requirements are that all of the facts to be used in the debate be part of general knowledge. The so-called opposition side, was responsible for refuting after the government has done presenting without any prep time, without any prior notice of the topic to be debated and go for it. It rewarded clear thinking, fast thinking, general knowledge and rhetoric skills. Williams had a very small team, but I was lucky that my class had another really strong debater. Amanda Amert my partner in those days. She's now a super fancy lawyer at Willkie Farr, not much of a surprise to me at all.

Amanda and I took our knocks learning from square one because there were no older people on the debate team. We just started it in our year or restarted it, I guess there had been a historical team and our senior year we were absolutely the top ranked team in the country and that ranking is becoming the so-called team of the year is determined in a similar way to the way that the top seed in the US bridge trials is determined. The major events all pay some number of points for first and second and so on down. The top five so-called markers, the top-five scores for each team count. One thing I'm proud of about that achievement is that the tournament season is about 20 weeks long, but Amanda and I just went to the first five tournaments.

We had five pretty good markers, and we said, you know what? We're going to be team of the year now. At that time we actually, after the first five tournaments, we had the highest score that anyone had ever had at the end of the season. We said, we're basically a lock to win now, and so we're not going to debate together at any of the other seasoned tournaments. We're going to go with novices and younger players. We spent the bulk of our senior year trying to make sure that the tradition of debate lived on at Williams after we graduated.

John: Wow. That's awesome, man.

Chris: We had a temporary win. The team did run on for maybe another four or five years, but I think after that, it faded out again, it's one of the issues with having a team for an esoteric activity at a small college. Where graduating class was around 500 folks. If you get a year where people aren't interested in it, you sometimes- it can be difficult to recover.

John: Does your mom like to take pride in your success in bridge? Does she like to take credit for that?

Chris: No. She wouldn't take credit for it. She wouldn't tell me this, but I suspect she'd probably rather that I had some real job that she understood. I think she resigned herself to bridge at this point, but probably would have been happier if I'd been a doctor or something.

John: Did she live in New York city?

Chris: Yes.

John: Your regular partner, your regular expert partner like Nash for big

events is Jan Jansma.

Chris: Yes.

John: I've played against him mostly in pair games, but I think he likes to laugh. I've

been to dinner with you guys. What's it like playing with Jan?

Chris: He's a little bit more intense in real life than you might think if you just met him

at the table, because he definitely can laugh at the table, but he's also a very

focused intense player, although he doesn't necessarily show that side as much to

the opponents. He's a really tough competitor and really excellent card player, he's

very tricky, so he's often trying to paint a wrong picture of the hand for the

opponents. That can be very tough to play against.

John: What about to partner, is it tough to partner with those types of deception

going on?

Chris: Yes. It can be, but there's this kind of an art to figuring out when partner might

not care, or when partner already knows what's going on. It does take a little bit of,

what I think of as a rubber bridge mentality. Meaning, when I was playing rubber

bridge as a young guy, the first lesson I learned was, assume whatever you need to

beat the hand from partner, and assume that partner also knows that and is not

going to necessarily signal you that that's the case.

Defend on that basis and signal around the other stuff which might or might not be

necessary. Sometimes, for example, I know that you, my partner, must hold the ace

of spades for us to have any chance to beat the contract. Let's say, it's three, no

Trump, and I can count nine top tricks for declarer if you have it.

I may hope that you're going to false card in spades to deceive declarer, or

alternatively, if it's a situation where I need to guess what to do, I might think that if

you did encourage you had ace-king or ace-queen or something in addition to show

me. There's that kind of extra level of inference that's baked into the signal. Of

course, both partners are not always on the same wavelength, but I think we're pretty

good at that high batting average.

John: That just strikes me as a next-level type of play that your partner knows that

you know that he has to have the ace of spades for us to have a chance. It's exciting

to hear about it. It's exciting to think that that type of play is going on, because it's not

something that- I don't think I've ever been in a situation like that, deeply into a hand

doing that. That's why people are hiring the two of you to play in big events.

Chris: It's interesting that you say that, the first part of it, because when I was

coming up, and again, playing a little bit of rubber bridge, that was considered an

advanced, but not expert rubber bridge play concept. think what has happened is

that we all play so much duplicate. There's very little rubber-bridge now, mostly

duplicate, and most duplicate is matchpoint pairs.

Obviously, this approach can cause issues in a match point pairs. You might need to

kind of more subtly signal, because the goal is not necessarily to beat the contract,

just to get as many tricks as we can. This whole idea of, I'm going to assume a

partner has X doesn't really work that well. I think most players start playing in some

local matchpoint event.

Then even if they graduate to playing team events, or even the major team events,

they still have that matchpoint orientation to their carding, and of course, the rubber

bridge players are giving up a lot of overtricks here, there, taking these sort of last-

ditch efforts to big contracts. I do think a lot of it is just kind of-- It's really hard to

have two completely different gears for matchpoints and IMPs for a partnership.

Obviously, there's going to be some differences, there's going to be some different

agreements, maybe even for a well-honed world-class partnership at the different

forms of scoring, but it's really hard to change your whole mentality. I think, in

practice, there's more matchpoints in our IMPs than there should be.

John: Can you think of an example of a hand where Jan was able to be deceptive.

Chris: We actually won a really close quarterfinal a few years back where the upshot

of it was that he had entry problems, but it wasn't obvious. Basically, he needed to

try to get a rough in the dummy. Basically, it's really complicated position, but he led

low from too little towards Queen and one, which now caused the opponents to play

a Trump from something, which allowed him to get to the dummy. It was like some

crazy head.

I didn't have to dig it up. It was a really potential brilliancy prize hand. If you looked at

it, for me, now maybe, I have that club in my bag because I've seen it, but it's the

hand where you could have imagined a really world-class technical card player,

staring at it for five minutes and not finding the solution, because it's not a technical

Play.

It's just realizing what the deal looks like to your opponents, at the same time, as

you're playing it yourself and trying to think about what the actual deal is. I do think

both of us have a bit of that. I'm pretty likely to spurn the best technical play and

exchange for information concealing plays, pass up, "Oh, you can play for three,

three," and the thing on side, or you can hope they don't find the switch and try to set

up a trick and another suit, so just obviously each situation is context-specific, but

just say, in general, I don't mind somebody saying after the hand to me, "Your play

was zero percent and you could have done this other thing."

If by zero percent, they mean I needed a missed defense, because in real life you do

often get missed defenses. Also, if you are known to be a tricky declarer, you may

pick up points on a normal hand where you're just doing something normal because

the opponents are worried that you've taken a non-technical way. I'm comfortable

with that.

John: How much is the quality of opponent or opponent specifically, does it go into?

Chris: Yes, it’s a really interesting question. I think it gets back to a more general

question, which is, how do you best outsmart some particular set of opponents?

Because when we sit down at the table, obviously we're trying to do well on our own

decisions, but also, we're trying to anticipate the opponent's thinking and be one step

ahead of them.

I think the key there is being exactly one step ahead of them. In other words, to take

a simple example, a dramatic false card isn't going to do you any good against an

opponent who's not looking at what you play, and maybe you throw away something

useful, or misled partner, or something. It's definitely true that the opponent's level

matters a lot, but there might be some plays that you would try only against strong

opponents, because the way I always like to think about it is having control of the table.

What I mean by that is, you're pretty confident that if you play a certain move, the

opponents are going to reliably play a move in response. You can have the thing

play out as you want. In certain ways, that can be easier against really excellent

opponents because they're going to be reasoning in a straightforward way.

It's easier to predict how they'll react to certain bits and plays, certain information

they perceive, whereas playing against weaker players, we might be able to get

away with some additional deceptions, but we also are likely to prevail if we just play

straightforwardly and don't mess up and don't miss any technical chances. I would

say it's not that there are more or fewer opportunities, depending on the level of the

opponent, just different opportunities.

John: Can you think of a time when you're opponent, that was really- you did great,

you did really well there, or is that something that's at the table during a big match?

Chris: In my experience, when people get swindled, they almost never make that

kind of comment, whereas, they may well make it for a great kind of technical play.

That's not just for kind of the obvious reason that maybe they're feeling a little stupid

and so, that they can say anything, but also because they know they messed up, but

a really strong player, who knows they've messed up, is not going to be spending a

lot of mental energy thinking about why they messed up, they won't necessarily know

at that moment have recall of exactly what their thought process was, and so they're

probably just onto the next hand most of the time, and that's obviously a critical,

critical skill in bridge if you dumped some IMPs, hopefully, the opponents will dump

some IMPs on the next hand, and you'll be back to even, and go from there.

John: Do you have any sort of cue phrase for yourself, or something you say to

yourself when you have a bad result?

Chris: Yes, it's interesting, I don't tend to be bothered by individual bad results. I

think I'm pretty good at not letting that affect my bridge game. If there are a few

results in a row, I'm definitely not an A+ in this category, and I can do some

steaming, but I rarely get upset about one hand unless there's something other than

the poor result that's making me upset. There's going to be so many IMPs

exchanged in any day-long match, for instance. 1, 12 IMPs [unintelligible 00:12:03] more or less is- it's significant, of course, but it's unlikely to be- it's much more likely to be matched deciding if the player who loses from it is affected by it, because then it can turn into maybe another eight IMPs of soft tilt, where I'm not going crazy and psyching trying to get my points back, but I'm just making inferior decisions, because there's a little piece of my consciousness that's still thinking about the previous board.

Usually, by the end of a set, I don't have a good short-term memory of what the

hands were. My partner will sometimes say, "Oh, did you like my four spade bid on

board five?" I'll say, "What was someone's hand?" If somebody- if they tell me what

someone held on the deal, I'll remember it right away, but I'm not- it's not sitting

there, the hand record is not sitting in the front of my consciousness.

John: When you're starting a partnership, is there something that would be a no-go, like if they want to play this I don't want to play with them?

Chris: System-wise, no. I've always played my partner’s system. That's just always been my way. When I started playing with Michael Rosen-- When I played with Roy, I played his relay notes and I just learned them and we tweaked them together. Over the years I think we made them a little stronger. We started with 100% of his notes. When I played with Michael Rosenberg, he sent me his set of notes with his previous partner. It was about 135 single-spaced pages or something like that, but I diligently learned it for that first tournament. I think by the time we got done, it was around 400 or so. Michael and I, we were scientific in those days. We had a lot of agreements.

With Jann, it's actually been a little closer to a blend. He really likes Polish club. He doesn't really care that much about other stuff. I said, "Okay, well, how about we do it this way? I'll play your Polish club stuff, your minors and you can play my majors." That sounded good to him. That's what we do. This is actually the most input I've ever had, but I'm really happy. As long as it's sensible, I'm really happy just to play whatever it makes my partner comfortable.

John: Did Roy design his system on his own or did he get it from somebody?

Chris: We were playing, I guess what is now become known as Transfer Walsh with a relay overlay on top of it. The Transfer Walsh ideas were originally Scandinavian, I think Swedish but wouldn't swear to it. I started playing them. I was actually playing those methods, I think before Roy got around to it I played with a New York partner of mine who had played a little with the Bureau and Valenia's, and so I think the Transfer Walsh drifted through in that way. The relays I think that was Roy and Bjorn designing it themselves, but I don't know for sure. I haven't seen it anywhere else. That's my best guess.

John: One question I have. I don't know about your father. We haven't talked about your father. Is he alive?

Chris: My dad died of a freak infection in 2016 where he was a pretty healthy guy who ran all the time. He was really looked out for himself. That was one of those- obviously, it's super sad to lose your father and in particular, it's sad when somebody really spends a lot of time preserving their longevity but basically he just got some really rapid infection and they didn't figure out what it was in time.

He was a great guy. He was an attorney by trade not naturally- and a litigator but not naturally argumentative. That was just his business. He was actually always very supportive of whatever I did as an adult. "Oh, you want to go trade on the floor right out of college instead of taking an office job?Great. No problem." "Oh, you're going to play bridge professionally? No problem." My dad went with the flow.

John: Your brother has played some bridge?

Chris: I have a younger brother, Tim. He's five years younger. He knows the rules of bridge. I've been trying to get him to take it up as a hobby, but he's very social. I think he hasn't found the time or inclination yet.

John: Do you have any projects, bridge-related projects, or what's on your horizon? How are you dealing with the coronavirus?

Chris: The last few months have been interesting. There has been a massive increase in demand for online playing and online teaching. I would say at the moment I'm mostly reacting to that demand. I'm trying to get everything scheduled in a sensible way. I think I'm now in the intermediate-term at roughly 50 hours of lessons a week or something like that. There's not a lot of time for side projects considering that I'm also the food shopper and chef in my family.

Given the quarantine, I probably cook about 10 meals a week probably ordering the other four or something like that. 10, 11 I cook. Between taking care of the food situation and playing bridge and finding time to have a nice glass of wine occasionally, I wouldn't say that there's a ton of time left for other stuff. The extent that I'm thinking about anything in a grand way, it's how to optimize the new formats that are available for online teaching. Zoom for example and additional functionalities of Bridge base, the idea is figuring out how to cram as much learning as possible into a short period without detracting from the fun part of bridge.

Because, first of all, many of the folks that I teach, they're not serious tournament players. Part of the goal for them is really to have fun in the lessons. For more serious students, maybe the lessons are a means to the end of competing more successfully, but a lot of folks don't have those kinds of ambitions, so I need to make it fun. I also know that it takes a whole lot of learning to become good at bridge. I'm still learning every time I sit down at the table.

My students really have a lot to learn. If I can make it fun for them and they won't burn out, they'll get to where they want to go a lot more easily. I've definitely been doing a lot of tweaking, trying different things. I have a bunch of different speeds now, if you will, depending on what I think might be appropriate for the individual student. I do not have any students who are just hiring me to do well in the local duplicate. Everybody has some interest in learning. There is an art to helping them as well as I can. That's what I'm working on.

[silence]

Chris: Well, you have a lot of talent. I think for you, improvement rates to be faster and easier than for many others. What I would tell you, and I think I've told you this before also in private, is if you really want to have success at the highest levels of the game- you've had a lot of success, so now we're talking about rarefied air already- but if you want to have success at the highest levels of the game, even if bridge is not your job, you have to treat it like a job. You have to work on it regularly, many days a week, whether you happen to be interested in doing it that day or not.

You have to study the parts of the game that are less fun to you, not just the parts that are more interesting. Just treat it as if it were your livelihood because right now the highest levels of the game are dominated by professionals. If we act like those professionals and assuming that we start with some reasonable degree of talent which you certainly have, there's a really good chance of, as I was talking about earlier, being able to hang in there with the best.

John: Who's better at barbu? You or Dana?

Chris: [chuckles] Hey, you have to ask Dana. You got to take a long comment on

that one.

John: I see you guys are on the team with Mig for the upcoming Barbu World Championship?

Chris: Yes. Mig, Dan, and I, and Mig's husband Pietro that doesn't really come to tournaments too often, so you really might not know him, we're all best of friends in real life. If we didn't have Coronavirus, we'd all be having dinner together at least once a week. We're very happy to find ways to socialize over the internet given the lockdown situations. Barbu World Championship is a bigger opportunity.

John: Is Pietro on the team?

Chris: Pietro is not a Barbu player, only when forced. He's one of these guys who teaches and directs bridge for a living. That's pretty much enough cards for Pietro. He's a real student of history and player of some of the intricate online video games. He has his own active interests. Whereas the other three of us could pretty much play cards from dusk till dawn and be happy.

John: Who's the other member of your Barbu team?

Chris: We've got a six-handed team. All folks that have played some bridge in their time. John and Mike Rice who are probably around my age perhaps but retired from bridge. They have real jobs and otherwise and so forth. We adopted a Belgian

because there's not enough Belgian for a national team. Steven De Donder who's actually a strong bridge player who's represented Belgium in the world championship a number of times. We basically have an all-bridge team. Team Bridge.

John: He's a strong Barbu player too? Steven.

Chris: Steven De Doner is arguably the best Barbu player in the world.

John: [chuckles] This is my standard question. I'm a little reluctant to ask but I'm going to ask you anyway. Are you better than Kalita?

Chris: [laughs] You asked everybody if they're better than Kalita? John: I started asking it, yes.

Chris: That's a funny question. I don't know [unintelligible 01:02:16] game that well. He certainly seems to be an excellent player. I don't think I'd be able to give you a good, informed opinion but they did win huge number of Reisingers in a row and then also beat us pretty recently in Spingold Quarterfinal where he played very well. I guess what I would actually like to say since I can't answer your question with a definitive yes or no is that you've mentioned somebody who plays the game the right way. That actually is the most important question that we are going to ask ourselves. Not on how good is so and so but do they play the game in the proper spirit, sportsmanship, and fairness as opposed to, I don't want to say, rules-oriented because people should be rules-oriented but very technical as opposed to being equitable. Ultimately, this is a game. We want to have it be fair and fun that he plays the game in that spirit, so that's better. The most important thing, right?

John: I think it a great note to end on.

Chris: All-righty. That was interesting talking to you, although maybe disturbing how much of my past you dredged up. I feel like I was on the psychiatrist couch more than the podcast but it was good. It was fun.

John: [laughs] Well, I will take that note. [laughs] Chris: All right.

[01:03:52] [END OF AUDIO]